Magic Bullet Game Analysis

Magic Bullet © K.Becker 2013

The medium of the videogame is set apart from other media by its highly interactive nature - people proceed in games by doing things, and this experiential quality lies at the very core of game design. It isn’t a game if there is no interaction – in other words the environment must change as a result of player actions. Videogames are popular precisely because they provide an experience - and games designed for learning can do no less. Thus, any epistemology of games must begin with the experience (Squire, 2006). With few exceptions most videogames also involve learning: a player finishes with a videogame when there is nothing more to be learned from it.

The medium of the videogame is set apart from other media by its highly interactive nature - people proceed in games by doing things, and this experiential quality lies at the very core of game design. It isn’t a game if there is no interaction – in other words the environment must change as a result of player actions. Videogames are popular precisely because they provide an experience - and games designed for learning can do no less. Thus, any epistemology of games must begin with the experience (Squire, 2006). With few exceptions most videogames also involve learning: a player finishes with a videogame when there is nothing more to be learned from it.

Both of these characteristics are key when designing games and both of these characteristics must be carefully considered when assessing games for learning purposes. Analyzing games and gameplay can help us understand how to build better learning games.

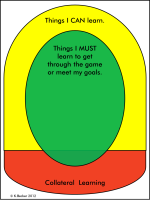

The Magic Bullet is a simple, flexible, yet powerful model we can use to analyze any game by looking at what players need to learn in order to play. All games involve learning, even when they aren't educational games. For instance, there are things a player must learn to succeed in any given game, and things they can learn, but don’t have to. This model offers a new lens for looking at how these things are balanced within a game, and what that means to the gameplay.

The outline below describes a simple yet effective model that can be used to help in the evaluation and design of digital games for commercial or for serious purposes (education being but one example).

All Games Teach

The path to the end of a videogame always requires the player to learn something: new facts, new skills, new strategies, and so on. This is true of all games, at least the first time they are played. There are some games that are what I call “Sorting & Organizing” games (such as Tetris and Bejeweled) where replayability does not rely on learning something new, but instead taps into our natural propensity to classify as a means of making sense of the world. For the purposes of this discussion, learning includes all possible learning that can occur (useful/useless, valuable/worthless, etc.). Learning is the supersetof education. 'Education' includes only that which a society deems valuable. Thus it can be said that all games require learning, even if they aren't in any way educational, and even if that learning has no use or value outside the game environment. It follows then that all games teach, since most single-player games are typically designed to be self-contained in that they are intended to be playable by a person who is alone and without help. This has implications both for game design generally, and for understanding games in a learning context.

Analyzing Games

There are still few approaches that allow us to analyse games in a way that is structured and that allows for comparison between different games or alternative designs of the same game. The Magic Bullet is a model for looking at what’s in a game and how the various parts are balanced, and it does that by looking at what players learn in and around the game. It is simple and flexible, and provides a new way to talk about game design.

Learning can be a bad word in commercial game design, but the truth is that all games involve learning. Looking at game design from the point of view of what players are learning in the game is a novel approach and opens up possibilities for perspectives that are not commonly viewed in game design today. This is true in all areas of game design, but it’s especially true in commercial game design.

This model is a new way to look at game design. Looking at how the balance of learning in a game is distributed can help designers decide if their design is on track to provide the kind of experience they’re hoping for and how they might shift things if it’s not.

Specifics: Analyzing Educational Games

This model can help educators formulate strategies for using existing games within a learning context.

When designing a new game or evaluating an existing game for its potential in a classroom or other formal educational situation it is critical that we understand what the game is intended to teach and how the game facilitates that learning. In fact, one of the things that makes a good game good is that it supports the learning players must do to win in effective ways. Many videogames already embody sound learning design principles (Becker, 2008) but there are still very few formal ways to assess and evaluate games. The one described here allows us to analyze how the various learning elements in the game are balanced, which in turn has implications for how engaging a game will be and how it might be used in the classroom. The model is a simple one as simple models have the advantage of being easy to remember and implement. It can be used to evaluate the design of a game not yet built but is also helpful in evaluating existing commercial games to uncover what kind of learning that game can facilitate. Evaluating a game using this approach can help educators create a better fit between identified learning objectives and the ways in which a game can be used to help achieve those objectives.

The Magic Bullet Model

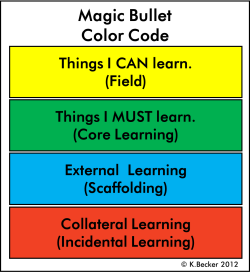

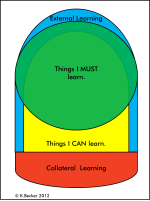

I originally developed this model while analyzing several strictly commercial videogames using another methodology I devised known as instructional ethology (Becker, 2007). In the process of producing extensive gameplay logs it became apparent that one perspective for looking at videogames is from the point of view of what players are learning as part of the game experience. It turns out that all learning in and around a game can be classified into four broad categories. It is known that not all learning in a game is necessary to win, although some always is. It is also true that sometimes learning occurs that was never intended by the designers, while other times players learn things outside the game that help them inside the game.

So it is that all learning in games can be classified as (non-exclusive) members of at least one of these sets. In the process of trying to show the relationships between these different sets, everal visualizations of the interrelationships of these four sets were created, and the final picture ended up being somewhat bullet-shaped. Thus, it earned the moniker “Magic Bullet”.

The four categories of learning are as follows:

- Things we CAN learn - as deliberately designed by those who created the game. This can include learning from all domains (cognitive, psychomotor, and affective) and all categories (remembering, understanding, applying, analyzing, evaluating, creating (Anderson, Krathwohl, & Bloom, 2001)). Learning in this category need not be related to any of the game’s goals. For example, it is possible to learn how to create new items and levels in Scribblenauts, but the game can be won without ever doing that.

- Things we MUST learn - this will almost always be a subset of the first category, and includes only those items that are necessary in order to win or get to the end. Since there is often more than one way to win a game these item must sometimes be qualified in the form of an if-then statement, such as “If we wish to pay off our mortgage in Animal Crossing then we MUST learn how to earn ‘bells’.” By contrast, planting fruit trees and selling the fruit is one way to accomplish this in the game, but it is not necessary as there are also other ways to earn ‘bells’ so it falls under the CAN-Learn category for this goal. However, if the goal is to collect all possible forms of fruit, then ‘planting fruit trees’ falls under the MUST Learn category.

- External Learning – This category includes learning that happens outside of the game: in fan sites, and other social venues. This category also includes ‘cheats’. One could argue whether or not this should be seen as a category distinct from Things-We-CAN-Learn. Cheats were originally designed into the game for testing purposes, and are often left in the game once it ships. Thus, they are deliberate design elements on the part of the designers, but are not really considered part of the normal gameplay. Note that some game designers may consciously put the cheats into play by assuming people will use them and designing accordingly but they are rarely, if ever, *required* to win, so they are almost never part of what we MUST learn. For many people, a game like the original Myst can not be won without turning to game guides that include spoilers.

- Collateral Learning - other things we can learn. These are not necessarily designed into the game, although sometimes designers may hope that players choose to take these up. For example, Tekken is a martial arts fighting game featuring a form of fighting called capoeira. As a direct result of playing this game, players may research and learn about capoeira, which is a Brazilian form started by slaves that combines dance, aerobics and music with kicking.

References

- Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing : a revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives (Complete ed.). New York: Longman.

- Becker, K. (2007a, June 25- June 29, 2007). Battle of the Titans: Mario vs. MathBlaster. Paper presented at the 19th Annual World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications (ED-MEDIA), 2007, Vancouver, Canada.

- Becker, K. (2007b, November 15-17, 2007). Instructional Ethology: Reverse Engineering for Serious Design of Educational Games. Paper presented at the Future Play, The International Conference on the Future of Game Design and Technology, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Becker, K. (2008). Video Game Pedagogy: Good Games = Good Pedagogy. In C. T. Miller (Ed.), Games: Their Purpose and Potential in Education (in press) New York: Springer Publishing.

- Squire, K. (2006). From Content to Context: Videogames as Designed Experience. Educational Researcher 35(8), 19-29.

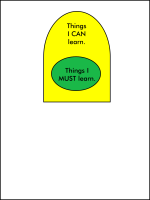

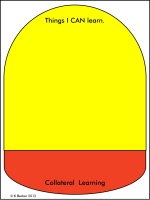

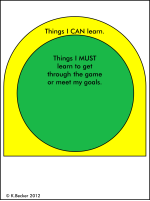

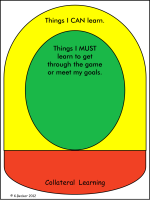

Image Legend

- Things I CAN learn

- Anything we CAN learn through the gameplay.

- Deliberately designed by those who created the game

- May impact success in the game

- Includes things designers *hope* people will take up

- Includes game-specific objectives as well as general ones

- Things I MUST learn

- Things we MUST learn to achieve our goals

- Deliberately designed by those who created the game

- Definitely impacts success in the game

- Needed in order to win or get to the end

- Should be a subset of the first category

- Required in order to achieve a specific game goal or in order to win

- External Learning

- Things we learn outside the bounds of normal gameplay

- Deliberately designed by those who created the game

- Not technically considered part of the normal gameplay

- May impact success in the game

- Includes social learning and outside communities

- Also includes Cheats

- Typically designed into the game for testing purposes

- Often left in the game once it ships

- Deliberate design elements on the part of the designers

- Collateral Learning

- Things we learn as a result of the game, but not as part of normal gameply

- Not designed into the game (at least, not on purpose)

- No impact on success in the game

- Other things we can learn

- These are not necessarily designed into the game, although sometimes designers may hope that players choose to take these up

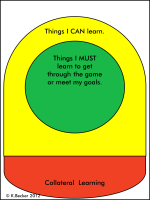

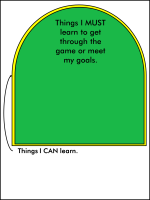

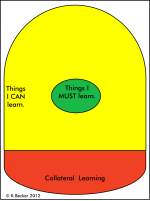

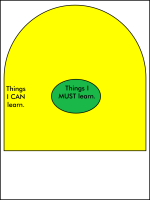

Sample Learning Profiles

- Nothing I MUST learn that is outside of what I CAN learn.

- Allows for learning outside of game and from cheats and community.

- Allows for learning outside of game and from cheats and community.

- Collateral learning possible

- Nothing I MUST learn that is outside of what I CAN learn.

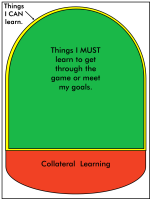

- Allows for learning outside of game and from cheats and community.

- can be very frustrating

- Often requires players to repeat plays and levels many times

- Challenging for some, frustrating

- Often requires players to repeat plays and levels many times

- Need outside help / resources to get into the game or progress

- design does not allow for or include external learning

- Need outside help / resources to get into the game or progress

- CAN still be good, but this has serious implications for audience and support requirements

- Very risky in serious games

Insufficient Internal Scaffolding

Insufficient Internal Scaffolding

- Need outside help / resources to get the intended message

- design does notprovide scaffolding

MUST learn is considerable component of CAN learn.

MUST learn is considerable component of CAN learn.

- can be good game

- edgames can fit in here

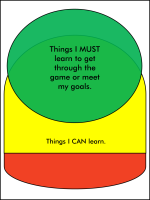

MUST learn includes collateral learning.

MUST learn includes collateral learning.

- Can make for great game

- Tends to worry traditional educators

- Can be very useful in serious games

- Games do not always need to be self-contained

- Nothing to learn that isn’t part of the ‘goal’

- Often edutainment fits in here

- Lack of collateral learning opportunities implies a single-purpose game (or an impoverished one)

- Lacks direction

- Aimless

- Toy, not game

- really nothing to hold player's interest

- often CAN needn't be much bigger than MUST in a short form game

- Can be great if carefully designed

- Must be designed as < = 5 minute game

- Many puzzle games are in this category

- No direction

- Even SIMs has some MUST learn

- Game on rails

- This is a toy

- Imbalance between CAN & MUST